Τhe 7th century Yassi Ada 1 shipwreck

- Theofano Moraiti

- Jun 9, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 4, 2024

In 626 AD, a ship carrying nearly a thousand amphorae struck a reef near the island of Yassi Ada and sank. The wreck was discovered by the Turkish diver Kemal Aras, who presented it to journalist Peter Throckmorton in 1958. Throckmorton, noting the distinctive features of the cabin and collecting ceramic samples, identified it as a valuable find from the early Byzantine period.

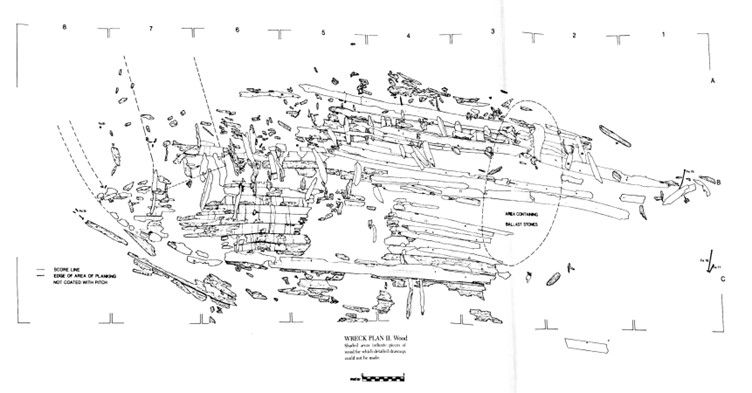

From 1961 to 1964, George Bass and his team from the University of Pennsylvania and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology conducted excavations at the shipwreck. The study of the wreck showed that the ship was small, moderately constructed, and carried 60 tons of cargo. The sinking of the ship on a steep slope, at a depth of about 32-39 meters, resulted in the stern section being buried in sand and preserved, while the bow, remaining on the surface, was not preserved. Although only 10% of the hull was recovered, the remains allowed for detailed reconstructions by Frederick van Doorninck and Richard Steffy.

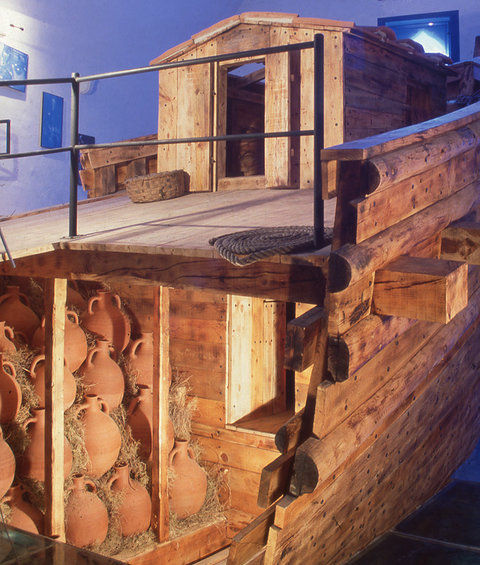

The ship was approximately 21 meters long and had a capacity of 60 tons, with a narrow and elongated length-to-width ratio of 4:1, where the maximum diameter was near the stern, giving it speed. Priority was given to resource conservation rather than aesthetics in the construction of the ship. Like its predecessors, the ship was constructed using the "shell-first" method of shipbuilding. A technical peculiarity was identified in the hull: from the waterline and above, the planks were nailed to the rising frames, transferring the power of the ship from the shell to the frame of the keel-frames, thus embodying, in this way, the transitional stage between ancient and modern shipbuilding.

The garboards were placed in the rabbets of the keel with mortise and tenon joints, which were then secured with iron nails. The planks of the hull were 130 to 250 millimeters wide and 35 to 42 millimeters thick, also joined with mortise-and-tenon joints, but without the use of treenails. These tenons were spaced 2,250 millimeters apart along the buttocks, 350-500 millimeters in the stern area, and 900 millimeters in the middle of the hull. The frame system of the hull was quite elaborate and consisted of short and long frames, overlapping scarphs, and riders. One in four frames was fastened to the keel with long treenails, while almost all the others with an iron nail.

The ship seems to have belonged to Captain George, as evidenced by the engraved information on the largest counterweight of the scale found. Besides being a priest, George was referred to in the inscription as a "ναύκληρος" (shipowner), a term indicating his role as the owner of the ship. The living conditions of the crew and their duties are inferred from findings such as shipwright tools and a fully equipped kitchen.

The concentration of ceramic vessels, cooking utensils, and other items indicates the presence of a kitchen in the lower part of the hull, further supporting the image of the ship as designed for long journeys and serving the sustenance of the crew and passengers. Among the cargo were found 11 different iron anchors, four of which were the main anchors of the ship. The large concentration of anchors has been interpreted in two ways: either the ship was initially equipped with enough anchors to avoid loss problems during the journey, or, in the event of a storm, it was necessary to deploy more anchors for the stability of the vessel.

The coins found in the ship date the ship's last voyage to 625 or 626 AD, indicating that the ship likely participated in military expeditions during the Byzantine-Persian wars. Van Doorninck suggested that the ship belonged to the church, given the captain's status and the construction designed to withstand long journeys and carry cargo.

The Yassi Ada 1 marks a fundamental change in the shipbuilding tradition of the Mediterranean, combining two construction techniques that represent the transition from ancient to modern shipbuilding. It is one of the most recent ships departing from the technique of mortise-and-tenon joints, replacing it with the use of nails, thus documenting a critical stage of the transitional period in shipbuilding between the 3rd and 8th centuries.

The significance of the Yassi Ada 1 as a product of Byzantine shipbuilding in the 7th century is extremely important as it marks the beginning of a fundamental change in the shipbuilding tradition of the Mediterranean. Whether the combined use of the two techniques on the same vessel served practical purposes of stability or was the result of experimentation remains unknown; however, the Yassi Ada 1 constituted a significant point in the transitional period of shipbuilding between the 3rd and 8th centuries.

Bibliography

Bass, G., F. ed. 2005. Beneath the Seven Seas, London.

Bass, G., F. and Van Doorninck, F., H., Jr. 1982. Yassi Ada, Volume I, A Seventh-Century Byzantine Shipwreck, Texas, USA.

Liphschitz, N. 2014. “Three Yassi Ada Shipwrecks, A Comparative Dendroarchaeological Investigation,” in Skyllis. Zeitschrift für Unterwasserarchäologie 14 (2), 203-207.

Pomey, P., Kahanov, Y. and Rieth, E. 2012. “Transition from Shell to Skeleton in Ancient Mediterranean Ship-Construction: analysis, problems, and future research,” in The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2012) 41.2, 235–314.

van Alfen, P. G. 1996. “New Light on the 7th-c. Yassı Ada Shipwreck: Capacities and Standard Sizes of LRA1 Amphoras,” in Journal of Roman Archaeology 9, 189-213.